The group

The Neurorehabilitation and Brain Research Group is a multidisciplinary team focused on assessing and promoting the recovery of brain function after an injury and on examining the underlying mechanisms of different brain processes.

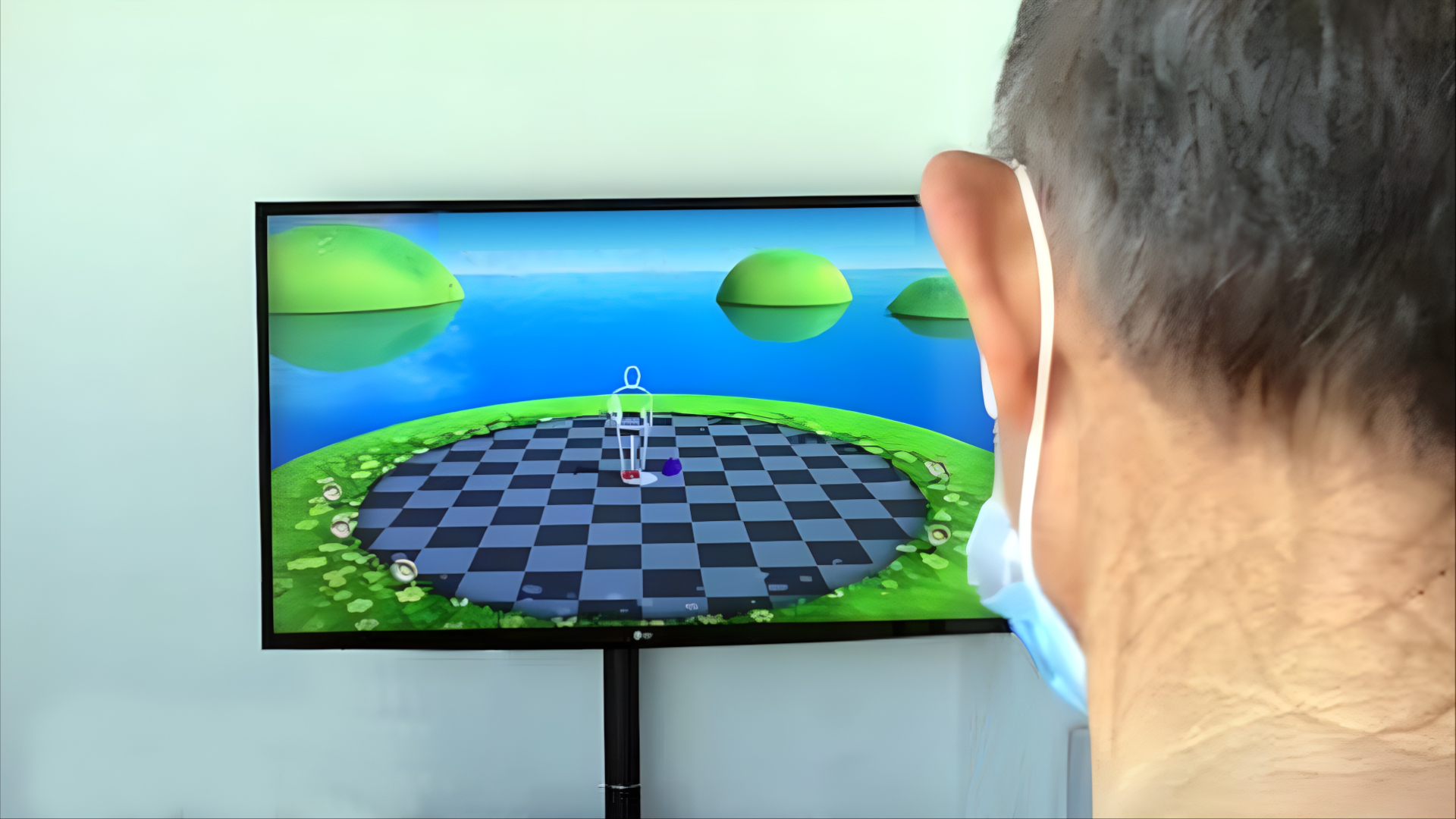

The main research areas of the group include but are not limited to the assessment and treatment of motor, cognitive and behavioral skills that are commonly impaired after an injury to the brain and on the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of consciousness after a brain injury. The research activities of the group usually encompass multimodal stimulation, including virtual reality and non-invasive brain stimulation; biomedical signal registration and processing, including electrical and hemodynamic brain activity and peripheral responses; and artificial intelligence, including machine learning and deep learning techniques.

The group is part of the Institute for Human-Centered Technology Research of the Universitat Politècnica de València (València, Spain) and maintains close collaborations with other national and international entities.

Areas

Balance

Upper limb

Cognition

Disorders of consciousness